Sci-Fi Debating Philosophy

Which Level Are You On?

Sci-Fi debating may be a game, an intellectual diversion, an utter waste of time, whatever you want to call it. But that doesn't change the fact that there are different philosophies one can use. And at the risk of being accused of elitism (not that it would be the first time), one can arrange them into different "levels" of rigour.

Level 1: Non-serious debates.

These are often characterized by levity, and while they can be a lot of fun, you couldn't really say that you learned anything through participation in one. A typical example looks something like this:

"Captain Kirk would be able to kick Han Solo's ass because his shirt will get ripped, and we all know ripped-shirt Kirk is invincible."

"Oh yeah? Well Han Solo shoots first, Special Editions be damned, and besides, he's also Indiana Jones, who defeated the entire Nazi Empire, found the Holy Grail, and recovered the lost Ark of the Covenant. Not to mention the fact that Han Solo was never seen doing PriceLine commercials."

The premiere venue for this sort of debate is WWWF Grudge Match: a site where silly contest scenarios are written up, described by competing writers, and then voted on by the general Internet population. Strongly recommended for comedic value, although it can get a bit repetitive after a while.

Level 2: "Author's intent" debates.

These ones put much more effort into the endeavour, but they employ a highly subjective and arguably no more serious method. Rather than treat the work of fiction as an object in its own right, these arguments treat it only as the fluid, subjective, and perhaps even grossly incorrect expression of the author's intent. Short of asking the author to comment personally on the matter, it is extremely difficult to even conduct any kind of meaningful debate on an issue such as this, particularly when its first tenet is that the fictional universe in question might not even be an accurate representation of the true subject: the thoughts of its author. Intent-based debates look something like this:

"There was no Endor Holocaust because the ending of Return of the Jedi is obviously intended to be a happy ending, with no impending environmental catastrophe from falling Death Star debris."

"So? Maybe Lucas intended there to be a darker subtext beneath the smiling faces; they might not have even realized what was about to happen. He allowed EU authors to write about the civil war dragging on for years and killing countless billions after ROTJ despite the happy ending, so why should this be any different?"

Notice how the argument is basically impossible to resolve due to its reliance upon "intent", and is thus basically useless for determining anything of value. Arguments like this could go on forever, because they are purely speculative with no real way of verifying anything, short of asking the author (which is generally impractical in many cases and may even be impossible in some cases). Indeed, even if you did ask the author, one would have to know exactly how the question was phrased, since the construction of the question can have a large impact on the answer, as any pollster will know.

Level 3: Sci-Fi Theology debates.

These debates (also known by the term "semantics debates") are characterized by a "religious fundamentalist" approach to the spoken word. Every line, every throwaway comment by an onscreen character is taken at absolutely literal face value, with no conditions, modifiers, extenuating circumstances, human error, or in-context interpretation. These arguments tend to look something like this:

"Commander Riker once said that lasers won't even penetrate the Enterprise's navigational deflector. Star Wars ships use lasers. Therefore, Star Wars ships are totally impotent against Star Trek ships. A Federation shuttlecraft could easily shake off the Death Star superlaser."

"Oh yeah? Well Darth Vader once said that the ability to destroy a planet is insignificant next to the power of the Force. Therefore, a Sith Lord should be able to wipe out the Federation with a thought."

"The Force doesn't count. Besides, in the DS9 episode "The Die is Cast", they said they were capable of destroying a planet's crust and mantle in six hours. This means a fleet of 30 ships must be capable of completely vapourizing all of that matter. Way more efficient than the Death Star, don't you think?"

"Oh yeah? Well in Star Wars, Dodonna said that the Death Star's firepower is greater than half the starfleet, which means the starfleet is around twice as powerful as the Death Star, which is in turn millions of times more powerful than the TDiC fleet".

What can one say about semantics debates that has not been said? The fact that the basic mentality is almost exactly the same as religious fundamentalist theology should tell you all that you need to know. While the method is not quite as insane here as it is in religion (after all, the documents of a sci-fi universe really were handed straight down from its Creator), the mentality of picking apart sentences in isolation and stretching interpretations from them regardless of context or consistency with visual effects (or sometimes even other dialogue) is no better. It's all well and good to throw in character dialogue as part of a list of evidence in favour of a theory, but it is much too flimsy a foundation to support an argument by itself.

Level 4: Jargon debates.

Also known as "I have more feature-bloat than you do!"

These are characterized by an obsession with the "advancement" level of science (whether real or imagined) and technology and the jargon terminology associated with it, rather than its actual performance parameters. They tend to look something like this:

"Star Trek ships are obviously more advanced. They have quantum torpedoes and transporters, both which require superphysics. Transporters require subspace technology, and quantum torpedoes require knowledge of zero-point energy quantum physics. Star Trek also has sentient androids; look at Data."

"So? Star Wars ships have turbolasers, which have the same basis as superlaser technology. And hyperdrive requires the ability to transition an entire ship into true tachyonic state in Planck time! And what's the big deal about Data? Sentient androids are a dime a dozen in Star Wars, but in the Federation, there's just one Data, and he can't even figure out the Chinese finger trap."

"Ah, but Data's brain is positronic! Does Star Wars have positronic brain technology?"

Notice how each side tries to prove that his side has some technological whiz-bang that the other side doesn't. Since different sci-fi universes employ different concepts for propulsion or weapons due to the nature of sci-fi, it is simply a given that different sci-fi societies will do things differently, have different kinds of toys, etc. It is not a given that any piece of technology which one side has but the other lacks is necessarily proof of superiority across the board.

Level 5: Objective-data debates.

These are objective, in the sense that for the first time, people start relying upon measurable quantities rather than silliness, speculation about an author's state of mind, semantics, or jargon competitions. However, the use of science is inconsistent at best. Sometimes it's valid, other times it bears no resemblance to any rational system of thought. Leaving aside attacks on the inclusion of a particular source (usually one that just happens to be devastating to the arguments of the person trying to declare it inadmissible), these debates tend to look like this:

"It takes 2.4E32 joules at minimum to permanently destroy an Earth-like planet, based on the Law of Universal Gravitation and some simple mathematics. The Death Star greatly exceeded this amount, because Alderaan blew up so violently that chunks were flying away at tens of thousands of kilometres per second."

"That's nothing. According to Graham Kennedy's website, measurements of the rate of contraction of the Genesis Planet in ST2, in conjunction with the TM's charted relationship of power to warp factor, lead to the conclusion to that the energy yield of the Genesis Device is 1E45 joules."

"That doesn't make any sense; if you pumped that much energy into the nebula it would heat and expand, not contract and cool! Where does all this energy go? What kind of lunatic thinks that a cloud of gas will contract and cool when you pour energy into it? Kennedy obviously has no idea what he's talking about. It's frightening that someone who says something like that is allowed to teach high school science.

"As I expected, I bring up a canon incident and you simply ignore it and attack the source. Concession accepted."

Notice the key element here: the data is objective, but the methods are all over the map. You cannot simply assume that conclusions are just as objective as the data from which they are derived; it depends on the person's grasp of logic.

Level 6: Scientific-method debates.

This is where you put it all together: you take objective data and analyze it in a scientific manner. This means that with movies, you would treat them the way an astronomer views pictures taken with a telescope. With official books, you treat them the way an anthropologist would treat historical sources: useful evidence but not enough to contradict archaeological discoveries. Please note that the scientific method is distinct from the actual specific details of science: it is a philosophical method which is useful for analyzing anything which is observable and rationally consistent. If there were a parallel universe to ours that had different laws of physics, the specific conclusions of our science might not necessarily apply but the scientific method would still be the best way to operate in that universe. For example:

Phasers completely vapourize people. Roughly 80% of a human body is water, and the energy required to vapourize 1 kg of water from body temperature is 2.4 MJ, so in order to vapourize 64kg of water (80% of an 80kg person's mass), you'd need roughly 150MJ. That's a lower limit. You rate typical hand blasters at only a few MJ. Therefore, phasers are obviously far more powerful than blasters.

150MJ, eh? That's rich: did you know that the muzzle energy of an Abrams MBT's 120mm smoothbore gun is in the range of 10 to 15 MJ? Do you really figure that a Federation hand phaser unleashes ten times more energy in one shot than a damned Abrams 120mm tank gun? Why don't they cause more damage when they hit anything but a person, then? Besides, what makes you think that they vapourize people? Where's the vapour? You do realize that the term "vapourize" requires that the object be converted from solid or liquid state to vapour, right? But objects which are hit by phasers don't vapourize; they seem to simply disappear.

Obviously, they "disappear" into vapour. You'd better go back to university and ask for a refund on that vaunted degree of yours.

So your explanation is that it turns into magical harmless vapour? Do you know what happens if you flash-boil 16 gallons of water? Anybody standing close to it would be either killed or horribly burned, moron. And in a confined space, the whole room would fill with scalding-hot steam.

So what do you think happens to people who get vaped, then?

We can't be sure, but there's no reason to assume that it's vapourization. Maybe it somehow sublimes the matter into neutrinos. Or alternatively, we know that transporters can make something disappear into their "subspace" catch-all term, only to reappear somewhere else in solid form without any net energy state increase at all. For all you know, phasers use the same mechanism, albeit without the re-assembly process.

Ha ha ha, that just means you get even more badly pasted. According to Lawrence Krauss in "The Physics of Star Trek", transporters require hundreds of megatons to work.

Oh right, so now hand phasers unleash hundreds of megatons? Why can't they wipe out entire cities and enemy formations with a single blast, then? I like the way you quote Krauss out of context: he's actually explaining why transporters can't work according to the sort of known mechanisms which would require such preposterous energy figures. Not to mention the way you seize upon this possible explanation as the only one. I'm just pointing out that numerous possibilities exist, all of which make more sense than your "flash-boil 16 gallons of water without making so much as a puff of steam" theory.

So maybe the material is vapourized and made to disappear with some other mechanism.

OK, time for a crash course in Occam's Razor: theory A says the target is made to disappear, either by sublimation into neutrinos or by one of these "subspace" excuses. Theory B says the same thing, but it adds "and it was vapourized too!" on the end. Why should we choose theory B, when all it does is add a completely redundant, unverifiable, unnecessary term on the end?

OK, so how do you know that this disappearing mechanism doesn't require more energy than vapourization?

I don't, but you bear the burden of proof to prove that it's high. You obviously don't understand the concept of lower limits. Besides, if this process took so much energy, why would phasers waste their energy on it when they could just hurl it at the enemy in the form of a laser or particle-beam?

Notice that we are not trying to force everything to conform to real scientific principles, as so many detractors of the scientific approach would suggest. We are actually forced to accept some kind of mechanism for making matter appear to disappear without a trace; we're only making the point that whatever this mechanism is, it obviously isn't vapourization, so you can't just compute for vapourization and then run with the resulting energy figure.

Naturally, scientific-method arguments tend to be more involved than other types of arguments. Ironically enough, Trekkies were the first ones to try and employ this type of argument, but they tended to be very sloppy. The first paragraph of the preceding example is fairly representative of what their arguments tend to look like: it looks scientific, but it doesn't bother to compare its physical predictions with observation. If you want to know whether your latest idea passes muster, try running it through the following checklist:

Question #1: Are the physical predictions scientifically valid and peer-reviewed?

It goes without saying that one's ability to technically analyze a phenomenon from limited observation is greatly improved if one has some kind of formal technical training in such matters. Self-taught technical experts are good at copying the style and mannerisms of the real article, but their methods are notoriously suspect, as you'll quickly find if you peruse creationist or alien-visitation websites. After all, anybody can read and quote from a science textbook, but not everyone can necessarily pass the final exams in science class.

As for peer review, the concept may sound a bit silly for a field of study in which there are no serious technical journals, but no human is perfect, and it certainly does help one's confidence (not to mention the credibility of his work) if others with formal technical qualifications have examined the work and found the basic logic behind key theories to be sound. Of course, one could point out that there is no peer review in a self-published document such as a website article, and this is true. However, the maintenance of a public forum upon which qualified people can post their comments compensates for this weakness somewhat (if for no other reason than publicly demonstrating that the people who disagree with the logic are lacking in qualifications), as does E-mail correspondence with qualified colleagues.

Question #2: Is the capability or phenomenon theoretical, or demonstrated?

"Vs" debating is rife with people claiming capabilities for one side or the other which have not actually been demonstrated, but which make sense according to their understanding of the fictional universe in question. However, it goes without saying that there is a considerable difference between "I think it should be possible" and "They've already done it four times."

An example of a strictly theoretical capability would be shooting an enemy grenade out of the air with a pistol. It is technically possible, but the history of combat is not exactly replete with incidents of soldiers performing such a feat. And of course, Star Trek fans are famous for making up new technologies on the spot, such as the "warp bomb" (an idea invented by Trekkies on alt.startrek.vs.starwars in which the warp field, which supposedly distorts spacetime, would be used to tear enemy ships apart).

Question #2a: If it is theoretical, how reliable is the underlying theory?

Not every undemonstrated capability is equally unreasonable, and this has to do with the reliability of the underlying theory. Obviously, any "theoretical" concept requires an underlying theory, but there is a vast gulf in reliability between (for example) the theory that the humans in "Star Wars" must periodically have bowel movements and the theory that Star Trek ships should be able to use warp fields to tear enemy ships apart in battle. Neither has been observed, but that doesn't make the two equivalent.

In the former case, the underlying theory (regarding human anatomy) comes from real-life, and while there are certain mentally disturbed individuals who might argue that "Star Wars" humans aren't really human, it seems reasonable to apply the "if it walks like a duck, talks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it's probably a duck" rule. However, in the latter case, the underlying theory has no real-life basis, so its validity is entirely dependent upon our comprehensive understanding of the operating mechanisms and physical principles governing the behaviour of a fictional technology. I should hope it is self-evident why the latter situation is significantly different than the former.

To use the phaser example argument from before, none of the predictions generated by any particular theory of phaser operation would be very reliable, because the mechanism is fictional and there are more questions than answers. So while one can say that it isn't vapuorization, one can't really say that it works a certain way, therefore we should be able to <insert idea here>.

Question #2b: If it was demonstrated, were there extenuating circumstances?

The phrase "extenuating circumstances" has taken on a negative connotation in recent times due to its utility as a universal "catch-all" excuse. However, the concept is still a valid one. For example, if a spaceship is heavily damaged and its capabilities appear to be very limited, this would be an example of an extenuating circumstance; the spacecraft might not be so limited without the damage. Conversely, if a spacecraft demonstrates a remarkable capability in a highly unusual environment (eg- some kind of anomalous, mysterious space-time distortion), it is rather questionable to assume that this capability is retained by the spacecraft at all times. The key is to establish that the circumstance in question should be reasonably assumed to affect the results in the manner prescribed.

Question #3: What is the variability of this capability or phenomenon?

OK, so let's suppose that we either have a demonstration of this phenomenon, or sufficient confidence in the validity of the underlying theory that we consider it reliable. We then come to the next question: what is the variability? In practice, repeatability is never perfect; even the most expensive CNC milling machine's repeatability is subject to a tolerance of several microns, and that's a high-precision piece of machinery employing very well-understood physical mechanisms under no-load conditions. Depending on what you're actually cutting with it, you might be happy with finish-machined tolerances as much as fifty times larger.

Nevertheless, well-manufactured equipment will typically have very low variability compared to the relatively loose requirements of a "vs" debate: for example, if a rifle fires a bullet at 1000 m/s, the next dozen bullets coming out of the magazine will probably have a velocity sufficiently close to that figure that the difference would not significantly change your conclusions about the rifle's effectiveness. But humans are a different matter entirely, and any "vs" argument where the human factor is present must take this into account.

A good example is marksmanship. When people attempt to "analyze" the marksmanship of soldiers in a movie, they often disregard the rather large variability of human physical performance. A good object lesson is the police video I once saw (on "True Stories of the Highway Patrol"; yes, I get Fox) of an officer and an armed suspect firing at each other repeatedly at a range of less than 3 metres. Amazingly, neither one was hit. But only a lunatic would take this incident and conclude that the effective range of a trained police officer or his gun is always less than 3 metres! Similarly, skydivers have survived falling from great height even when their parachutes failed to open; once again, while this is a "demonstrated capability", only a lunatic would actually conclude that humans can typically survive falling out of an airplane without a working parachute.

Another good example is phasers: their behaviour varies so much from situation to situation that one is forced to conclude that either the writers are incompetent (if one does not suspend disbelief) or that phasers are extremely sensitive to environmental conditions or some other factor we are unaware of.

Question #3a: If the variability is large, are we using the mean, or the extreme?

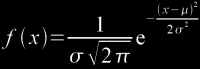

The following is what statisticians call a "normal distribution". By that, we mean that it can be approximated with the following function:

In this equation, σ is the square root of variance and μ is the mean (more commonly known as the "average"). When plotted, you get a general shape, centred around the mean, which looks something like this:

As per the curve (also known as the "Bell Curve"), the majority of incidents will occur in the "bulge" in the middle, but there will also be incidents at the extreme high and low end. The majority of phenomena which are influenced by small and random factors tend to produce a statistical distribution like this (this is a mathematical principle known as the "central limit theorem"), so many human performance parameters fit this probabilistic function quite well. None of this will come as news to those of you who have studied statistical functions in any capacity, and this information can easily be found in any basic math textbook. However, it is the application of this principle where a lot of "vs" arguments fail, by virtue of completely ignoring it.

Even the best will be guilty of this on occasion, for reasons which are quite understandable; after all, in order to account for variability requires extra work, and nobody likes to do extra work. However, the fact remains that when "vs" arguments devolve to debates involving human behaviour, the use of so-called "key incidents" to establish general performance parameters is a highly questionable tactic.

The instant human behaviour (or the behaviour of any highly unreliable piece of technology) comes into play, you have to recognize that two widely different incidents are not necessarily a "contradiction"; they may simply be examples of the normal distribution function in action. As an example of the application of variability in sci-fi analysis, consider the common belief that Imperial stormtroopers in Star Wars are horrible marksmen. One can find numerous specific examples of poor shots from stormtroopers, just as one can find examples of good shots from stormtroopers. Are these contradictions? Bad writing? Extenuating circumstances? Or are they merely different points on a Bell curve?

When variability is high, some sci-fi debaters virtually make careers out of cherry-picking good extremes for their preferred sides and bad extremes for the other side rather than settling for the mean, and others make a career out of accusing people of doing this even if it isn't true. Learn to recognize when it's actually happening. And remember that if you're wondering how something or someone will behave in a hypothetical situation, you should be looking for the mean, not the extreme.

Conclusion

There are those who will very stridently argue that it is wrong for me to arrange the various philosophies of sci-fi analysis into hierarchical levels and subtly imply that one is better than the other. They would be correct; it is wrong to subtly imply such a thing because it is better to come right out and flatly state such a thing: to put it quite bluntly, the less intelligent and knowledgeable you are, the more likely you are to stay on the lower levels. The only exception to this rule would be Level 1: non-serious debates. If someone wants to use levity for pure recreational value, that is considerably different than taking the subject matter seriously but still conducting your analyses in a juvenile or unresolvable fashion.

If you want to debate at the higher level, please keep in mind that it takes more work than the others and raises the stakes: after all, the more work you put into something, the more embarrassing it is to screw up. But if your opponent comes at you on this level and you can't or won't rise to it in order to meet him, it reveals your limitations in a very public way.